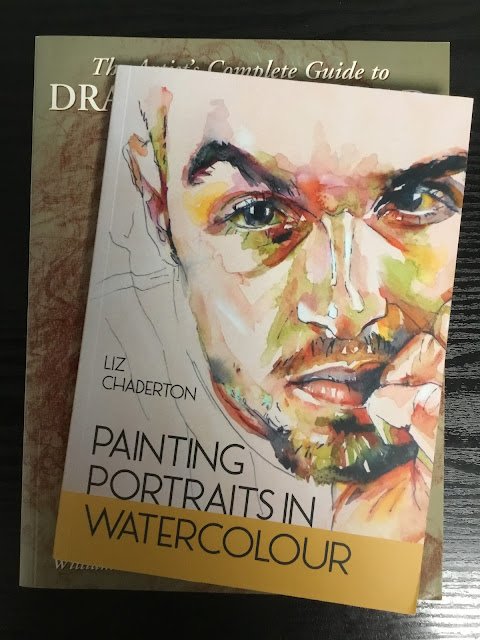

With the art studio out of bounds while building work is going on, there’s not been much painting action going on lately so I thought I’d use the time to buy and read a couple of art books. I’ve just finished this one. It’s a 112 page paperback, smaller than 7×10 inches. Before you say anything, I have to point out that this is a Liz Chaderton book, so tips are tightly packed in here and it feels more like a 200 page monster. I bought this book as I do want to start painting watercolour portraits at some point and am looking for the right book to get me there. I wasn’t impressed with David Thomas’ book, which I’d heard was the best out there. Liz’s book looked interesting in the flickthrough that she posted on YouTube, so I thought I’d give this one a go.

The book has eight similarly sized chapters. First up is a chapter in transferring the image to paper. As well as the grid method, there’s talk about tracing paper, carbon paper, an alternative gridding method and light boxes, along with what must be every possible tip on using all those techniques. Nothing really new to me but I’m already impressed with how Liz can give as many tips in one paragraph as other authors do in five pages. And, most importantly the message is coming through to me that using a grid isn’t cheating. For portraits anyway.

Then we have three chapters on painting portraits in watercolour. There’s a chapter on monotone, value driven portraits. Then one that’s value driven but with colour, very abstract and allowing the colours to mix on the paper. And then a chapter on painting in multiple monochrome layers. The real point is that value is much more important than colour. When colours are introduced, it’s first in an abstract way as a mood setter and only later as a tool to approximate actual colours. Very clever. There are seven demonstrations in these three chapters. Unlike demos in other books, they’re described in the main body of the text and illustrated by scattered photos, rather than described in text underneath a load of regularly organised photos. I honestly haven’t decided which I prefer. These three chapters also include a scattering of the sort of introductory tips that might appear in an opening chapter in other books. Stuff like equipment, colour theory, brushstrokes. Somehow scattering them among densely tipped chapters makes them feel like less of a space waster than they would have done if all gathered together into one chapter.

Then we get a couple of chapters on pushing it further. First there’s a chapter on line and wash portraits. And you know what? I don’t mind this. I actually welcome it and think it was a smart idea to include it. It works for landscapes and presumably for figures so why shouldn’t it work for portraits? And then we get a chapter on mixed media. Slightly less interesting to me but not a killer. There’s some stuff on using pastel pencils on a watercolour portrait that would probably work with coloured pencils or charcoal pencils. Then some stuff on collages, with a lot of ideas, that could apply to any watercolour painting. Then a weird idea with ink and gouache but no watercolour – Liz’s first misstep so we’ll forgive her. There are five demos in these two chapters which, apart from the one with ink and gouache are 90% about reinforcing earlier lessons and only 10% on stretching further. So even if I wasn’t interested in mixed media or line and wash, these chapters would still add value.

And then we get to the two most tip–packed chapters that I’ve ever read. They’re as packed as the compact notes that I make on these books after I read them. First up is a chapter on “special challenges”. It’s one huge brain dump of tips on how to paint old people, kids, beards, hair, eyes, eye brows, ears, wrinkles, noses, mouths, hands and teeth. There’s also something about the three bands of colour across the face that I first read about in

Colour And Light by James Gurney.

And then we get a chapter on “achieving a likeness”. Actually it turns out the the first chapter on transferring images was all about getting a likeness. This chapter is about drawing freehand if you don’t like the ideas in that first chapter (or if you think they all amount to cheating). So here we have all the usual rules about how the features on the face relate to each other. The face being five eyes wide, that sort of thing. There’s also a reminder about perspective and how things move around and resize when the head is moved. And a demonstration of painting from an upside down photo, a great idea, albeit one that Liz admits we’d have all seen before.

And to finish the book there are a couple of pages of interesting online resources for source photos, artists to check out, etc.

Having read the book, made notes and written up this review I’m feeling knackered. I can’t believe this book is only 112 pages long. Liz isn’t one to waste a word on fluff – she just bangs the ideas out like a machine gun. It’s something worth being aware of. This isn’t one of those books you can skip through, knowing that you’ll be able to focus in on the big ideas when they come: there’s just a constant stream and you have to be switched on when reading this one. I tip the chapeau to the author.

Is it the answer to all my prayers though? Yes and no. I don’t think this is the perfect standalone book on watercolour portraits. For me, it jumps too quickly into the monotone paintings without making sure that the reader can look at his source and identify the value pattern that he needs to be painting. I think there are also some important value–based tips later in the book that the reader could do with knowing before starting on the monochrome paintings. Like how the bottom lip tends to be highlighted and defined only by the shadow underneath. So, no, not the perfect standalone book I was hoping to find.

On the other hand, this is a brilliant tetris book. A tetris book is one that fits perfectly with another book to create something truly monstrous. Remember

that Bill Maugham book that I raved about? If you want to paint watercolour portraits, that’s the place to start. There’s no mention there of watercolours from what I remember but there’s everything about value patterns and how they appear on the face. After reading that book, Liz’s book is perfect for filling in the holes and extending all those lessons to painting in watercolour. Obviously better if you already know how to use watercolours and how to draw, but otherwise Bill is the perfect prerequisite to Liz. Having read Bill’s book, though, Liz has left me eager to get started on watercolour portraits: I can’t wait to get started.

Because Liz’s book struggles to stand alone, I couldn’t give it five palettes at first but in the couple of months since reading this book, I’m finding that it’s made. Huge difference to my watercolour portraits. I therefore take great pleasure in bumping it up to five palettes. Great pleasure because Liz runs a free YouTube channel as well as painting and writing books and I can tell from her videos that she’s a genuinely nice person who deserves every success and I still feel guilty about my review of her previous book. Just make sure you also check out Bill Maugham’s book.

🎨🎨🎨🎨🎨

<Edit: if you prefer to paint portraits in realistic colours, rather than impressionistically, I’ve since discovered

a book by Hiroko Shibasaki that would be great for a new watercolour portrait artist. For someone like me, though, it’s Liz and Bill all day long.>

Leave a Reply